- Home

- Douglas Niles

Fox at the Front (Fox on the Rhine) Page 3

Fox at the Front (Fox on the Rhine) Read online

Page 3

“Yes, sir, you are finished,” said Peiper coldly. His grossly insubordinate tone and manner temporarily surprised everyone in the room, including Guderian, who was taken aback momentarily. Exploiting the moment, Peiper continued. “I am now acting under the personal orders of the führer, who radioed me earlier this morning.”

As it was well known that Peiper had been Himmler’s adjutant, eyes turned to him. “Führer Himmler is aware of the alleged surrender, which is a flagrant violation of the military oath each of us has taken to the State and the Party. He rejects the surrender and orders us to take action. He states that anyone obeying the surrender order is guilty of the crime of desertion under fire.”

Guderian’s rage was now full-blown. “Shut up and sit down, Peiper. You and that arschloch Himmler may be willing to turn Germany over to the schweinische Russian hurensohnnen, but I’m not.”

Peiper went white in the face. “The führer is in charge of the army and the nation, not you! You will speak of our führer with respect, not in that filthy manner!”

“Sit down right now before I have you arrested and shot!” screamed Guderian. “I am commander of Sixth Panzer Army. Don’t you dare talk back to me in that tone of voice!”

“You have forfeited your rights as a commander by this cowardly and traitorous act!” shouted Peiper in return, his own temper exploding.

Caught up in the drama, everyone else around the table waited in silence for the conflict to resolve.

“Cowardly?” yelled Guderian in rage. He started striding toward Peiper, his fists clenching, ready to enforce his dominance of the room.

But Peiper’s gun was already in his hand.

ARMEEGRUPPE B HEADQUARTERS, DINANT, BELGIUM, 0709 HOURS GMT

Generaloberst Doktor Hans Speidel, Rommel’s chief of staff, had been leading a double life for more than a year now. When he first was recruited into the conspiracy to assassinate Adolf Hitler and replace the Nazi regime with a new German government, he quickly became a power in the organization. Regardless of how morally upright, how idealistic, or how determined the many conspirators were, they tended not to be outstanding leaders. After all, to be a conspirator meant that one was dissatisfied with the regular order of things, not a part of the power structure, not in charge of that which one wished to overthrow. Such people were generally not found at the top of the organizations of which they were a part.

Speidel was a pragmatist above all else. There were many high-ranking German officers who were aware that their nation was heading toward certain and complete destruction, many who could see that Adolf Hitler and his most intimate associates were responsible for that destruction, and even many who understood at least some of the crimes against humanity being committed by the Nazis. But for many, the path of least resistance meant to follow their soldier’s oath, to continue in their hopeless jobs, to comply with or at least to avoid knowing too much about such things as the ongoing liquidation of the Jews.

Speidel was different.

As was often the case, Rommel’s genius had astonished his chief of staff. Surrender reconceived as an offensive move! How brilliant and how obvious, especially in retrospect. Now it was up to Speidel to perform the detailed maneuvering within Rommel’s broad strategy. He would get Patton alone and give him the story of the conspiracy, and then he would somehow find an opportunity to tell the story to Eisenhower. For Rommel’s surrender was only the opening move—Speidel was still committed to a new Germany, a free Germany, with the right leadership at the helm.

And Speidel fully intended to be one of Germany’s new leaders, alongside the Desert Fox once again.

Now he had a perfect chance to prove his value. He had seen orders dispatched to the various components of the army group; he had marked the latest positions on a map of Belgium; he had seen to the functioning of the entire staff. Rommel had been out already this morning, supervising the conduct of the surrender, while Speidel remained here, behind the scenes, making sure that everything functioned. Who knew how long the field marshal would be making his rounds?

But that was all right, as it should be. The great man would make his presence felt, that powerful force of personality that caused things to happen just by being there. And Speidel would see that Rommel’s orders were carried out.

THE WHITE HOUSE, WASHINGTON, DC, 0753 HOURS GMT

A hand shook Hartnell Stone’s shoulder. “Mr. Stone?” A muffled sound resulted. A second shake. “Mr. Stone!”

“Mmmph?”

A third shake. “Mr. Stone, the president is awake.”

“What time is it?”

“Almost three o’clock in the morning.”

“All right,” he replied, voice thick. “Let me throw some water on my face and I’ll be right down.” He sat up slowly on the office sofa and bent down to fumble with his wing tips, moving, but still mostly asleep. His eyes scrunched tightly shut when the aide turned on the light, then opened very slightly, sticky with sleep. The aide stood patiently by as Stone tied his shoes, stood up, and crossed the hall to the men’s room.

The cold water splashing on his face woke him more fully. He combed his jet black hair, pulled up his Windsor-knotted tie, and retucked his white shirt. He smoothed his shirt and trousers as much as he could, but he was still rather rumpled. Well, it couldn’t be helped. He was on call, and the president was awake and in his study, an oval room—variously called the Oval Room or the Oval Study—on the second floor of the White House next to the president’s bedroom.

This room, distinct from the president’s formal Oval Office on the ground floor of the West Wing, was the actual nerve center of the Roosevelt presidency, a chaotic, messy room filled with cast-off furniture from other federal agencies, sofas, card tables, ship models, bookcases, and anything else that had caught FDR’s fancy during three—and now a fourth—terms in office.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, thirty-second President of the United States of America, looked old, tired, frail. His skin was white, nearly translucent, like crumpled parchment. Only the inner circles of the White House knew just how perilous the president’s health had become, but anyone with eyes who saw the president in candid moments could tell that he had aged terribly. His hands shook, his memory faltered on numerous occasions. He had an increasingly hard time sleeping in the cold and damp Washington winter—indeed, anywhere except for his Warm Springs retreat.

The study looked out onto the south lawn of the White House in the direction of the Washington Monument. The skies were clear and the gibbous moon was bright. The white marble obelisk shined silver in its light. In the room, a single lamp cast a thick yellow light onto the old man in the wheelchair.

“Good morning, Hartnell,” the president said. His voice was thin and dry. “I see they sent you in to keep an old man company.” He gestured at the table with the lamp. His cigarette holder sat next to an ashtray, with a pack of cigarettes beside it. Stone fitted a cigarette into the holder, gave it to the president, and picked up the heavy silver table lighter so the president didn’t have to bend forward. Roosevelt’s hand trembled as he lit his cigarette.

Stone stood as Roosevelt smoked and looked out the window across the broad expanse of the Ellipse and Mall. He still felt a sense of awe in the presence of the president, even though he had known him since childhood as “Uncle Franklin.” The president was not actually a relative of his, but Stone’s father had been a longtime friend. Hartnell had grown up knowing the aristocratic governor of New York even before he had been stricken with polio. The personal connection was critical. It was, after all, how a man in his early twenties with no experience beyond a Harvard degree gained a presidential appointment. He felt no guilt about that; it was the way the world worked, the way it had always worked. After all, personal connections were the only ones on which you could truly depend.

“There are times I almost think I can see the artillery fire,” Roosevelt said. His voice was weak and distant, not the mellifluous tone with which all Americans had b

ecome familiar. “The war is that way, you know.” He pointed his cigarette holder out the window in the direction of the monument. “While you and I sit in peace and quiet, there is a battle raging over the horizon. Boys are dying in the mud right now. Boys I sent.”

There was a long pause, and Stone waited patiently. He knew there were boys dying in the mud, and not infrequently he felt guilt because he was not one of them. He had been in ROTC at Harvard, and held a current Army commission as a major, but he hardly ever wore a uniform. He had served on the SHAEF staff in England for a year, as one of hundreds of officers preparing for Operation Overlord, and had even set foot on the beaches of Normandy a few weeks after D-Day. That was as close as he’d come to combat. Soon thereafter, he had been transferred to Washington, to the White House staff, as one of the many aides surrounding the president.

“Hartnell, pick up that folder on my desk. No, the other one. That’s right.” The folder was labeled TOP SECRET, as were others on the president’s private desk. Although Stone had as much curiosity as any man, he accepted the need for secrecy. He handed the folder to the president, but the president waved his hand. “No, open it. Read it.”

There was a long telegram in the folder, from the current SHAEF headquarters in France. Stone scanned it quickly. His eyes widened. “Surrender?”

“That’s what it says,” Roosevelt replied.

Stone kept reading. “But nothing has been confirmed.”

FDR chuckled. His voice warmed as he spoke. “That, my boy, is the bane of my existence. No one wants to go out on a limb even so much as predicting that the sun will rise in the east in a few hours. No, it’s not confirmed. Even so, it opens a host of possibilities. It could cut months off this terrible war. I might yet live to see its end.”

“Of course you will, sir,” Stone interjected.

“Ah, my boy, the certainty of youth. No, I’m an old man and just about used up. At least Uncle Joe did me a favor by dropping out of the war when he did.”

“Sir?” It was well known in the White House that FDR had been furious about the Soviet double cross, the separate peace Himmler had negotiated after the assassination of Adolf Hitler.

“We would be having another conference about now—Stalin, Churchill, and I—and I don’t think I could survive another long trip. Now I can stay home and husband my strength just a little longer. A little longer …” His voice grew bleak and thin again. “If only I could sleep … .”

Roosevelt’s eyes were focused far away, past the monument. “Do you know what I most wanted, Hartnell, my boy?”

“No, sir.”

“I wanted to make this war the end. The last one. And for that I needed Stalin at the peace table. Without him, all we will get is a temporary respite. Germany defeated, of course, and Japan not far behind. Then, as soon as everyone recovers a bit, on to World War Three. Democracy versus Communism.” He shook his head. “I would have given Stalin almost anything to avoid a third global war. I’m not sure humanity can withstand another such conflict as the one we are about to conclude. The progress in weapons has been terrible … terrible … .” His voice trailed away, and he was lost in thought. Stone continued to stand, watching, listening.

Roosevelt’s next words came as a whisper. Stone strained to catch them. “Terrible weapons. And shortly we will have the most terrible of all.” Another pause, lasting more than a minute. Stone grew more and more uncomfortable in the silent room, illuminated only by the single lamp.

“Communists believe in historical inevitability, you know,” Roosevelt said, his voice returning to a slightly more normal volume again. “I had hoped that would be enough to gain Stalin as a partner in peace. After all, he believes time is on the side of the Communists. Give them the shattered nations of eastern Europe to digest, and that would keep them busy for decades. It would let them draw comfort from ‘historical inevitability’ while we rebuild the West. We could let our two systems compete in how well they serve their people, and the conflict would resolve itself without a need for another war.”

“Will we win?” Stone asked.

Roosevelt’s eyes focused on him, and his famous jaunty grin briefly illuminated his face. “Who cares, my dear boy? Who cares? If it becomes clear that one system benefits humanity better than the other, whichever it may be, then let that one triumph. We Americans are pragmatists, you know. The proof of the pudding is in the eating.” His chuckle was dry, and drifted away. His expression became distant again. “A peaceful conflict is infinitely preferable to war, to more death and destruction. But Stalin couldn’t see it that way. He thinks I will reward him after he deserted us, or be willing to simply turn back the clock and behave as if nothing has happened. But I cannot. As much as I despise war, I do know how to wage it … .” His voice trailed off again. “So much death. So much death. And now I must order more.

“What I would have given Stalin freely as a partner I cannot give him as a reward for his betrayal,” Roosevelt kept on. “I thought we might have to go directly from this war into the next war, but if this surrender is real, there is hope. We can reach Berlin before Stalin’s armies, and we order him back to his own lands without a new war.” His voice was a whisper again.

“And if he won’t go?” asked Stone, his own voice now a whisper. He had a good idea how strong the Soviets were, and a detailed understanding of how strong the Western Allies were. The Western Allies would not have the necessary might to enforce Roosevelt’s order, not without the horrible new war Roosevelt hoped to avoid.

The President of the United States looked grim as he turned to look directly at Stone. “He will go. Believe me, he will go.”

ARMEEGRUPPE B FIELD HOSPITAL, NEAR DINANT, 1442 HOURS GMT

The short, pudgy man had been pacing back and forth in the waiting area for the past hour, periodically removing his round, wire-rimmed glasses to polish them, then slipping them back on over his watery blue eyes. He could overhear the occasional whispers. “That’s the man who saved the field marshal’s life?” He knew he didn’t look the part of the hero, and he didn’t feel the part either. But he had indeed managed to chase a trained SS assassin through dark, battle-strewn streets, then kill the killer before he could end the career of the Desert Fox.

Colonel Wolfgang Müller was in charge of supply operations for Armeegruppe B, and until the previous night had never fired a gun in anger or at a living target. Nervous around superior officers, not particularly assertive, Müller survived because he was good and careful with his work.

“Herr Oberst?” asked a doctor just coming out of the operating room, pulling off spattered gloves as he walked.

“Is there news?” Müller responded, a combination of desperation and concern in his voice.

The doctor’s face was stern, his words carefully chosen. “I’m Dr. Schlüter. Yes, Herr Oberst. Your friend is in very serious condition, but he’s past the worst of it. The prognosis is only satisfactory, but I have good hopes for this one.”

Müller let out a deep breath he had not been aware he’d held. Relief flooding his body, he suddenly remembered to ask, “And the feldwebel—the field marshal’s driver? How is he?”

“You mean Mutti?” Schlüter smiled. Everyone knew Mutti, Carl-Heinz Clausen, Rommel’s driver, orderly, and mother hen. “The wound was less serious than it first appeared. His condition is good. He’ll be up trying to help his wardmates before too long. We’ll probably have to tie him down to the bed to give him time to recover.”

Müller smiled broadly. Hearing the news took a huge burden off his shoulders. This was good news all around in a time when good news seemed increasingly scarce. “Is it possible to see either of them?”

“Briefly,” replied the doctor. “Follow me, please.”

Müller followed the doctor through double swinging doors into a long hall. Doctors, nurses, and aides of all sorts were bustling around, but it was only ordinarily busy rather than utterly chaotic—the worst of the battlefield wounded had been dealt w

ith, and now the hospital’s business had returned to a more normal state.

Carl-Heinz was in a large, brightly lit ward filled with heavily bandaged soldiers. Some were sitting up; others were even ambulatory. Hospital machinery surrounded the feldwebel’s bed, an IV drip fed into his arm. Müller was shocked at how pale and drained his face had become. Carl-Heinz was normally filled with life and confident energy, and to see him like this was unsettling.

As Müller approached, Carl-Heinz smiled, and something of the old energy showed through in his face. “Guten Tag, Herr Oberst,” he said. “Pardon me for not saluting. My salute hand is temporarily occupied.”

“How are you, Feldwebel?” Müller asked. “The field marshal asked me to make sure you were all right, and to tell you that he would be here to visit you shortly, as soon as he can. He depends on you utterly, you know.”

Carl-Heinz smiled. “I know he does. And now the rest of you will have to take care of him until I get back. You tell the field marshal that he is to get a good night’s sleep and a real meal into him before he comes traipsing over here. I won’t have him straining himself, you know.”

“I’ll relay your orders to the field marshal as soon as I see him.” Müller smiled in return.

“I can get back to work soon. It will be in a couple of days, all right? Definitely no more.”

Müller nodded. He knew it would likely take more than a few days before the brave feldwebel was back at his post.

“Herr Oberst—that was a heroic act you did, killing Brigadeführer Bücher before he could assassinate the field marshal,” said Mutti. “Thank you.”

Müller waved off the thanks with an embarrassed shrug. He still could hardly believe he’d done the act, and the thought brought back the sheer terror of the event. “I—er, well—it was …” He stammered for a minute, then simply replied, “Er—thanks. Is there anything I can do for you, anything you need? Something to eat, perhaps?” Müller remembered that there was still some cake his mother had sent, one made with real flour and real eggs.

Feathered Dragon mt-3

Feathered Dragon mt-3 The Kinslayer Wars

The Kinslayer Wars Black Wizards

Black Wizards The Heir of Kayolin dh-2

The Heir of Kayolin dh-2 The Crown and the Sword tros-2

The Crown and the Sword tros-2 Realms of Valor a-1

Realms of Valor a-1 Wizards Conclave aom-5

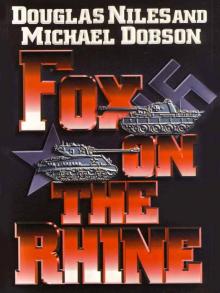

Wizards Conclave aom-5 Fox On The Rhine

Fox On The Rhine The Heir of Kayolin

The Heir of Kayolin Fox at the Front (Fox on the Rhine)

Fox at the Front (Fox on the Rhine) Measure and the Truth tros-3

Measure and the Truth tros-3 Emperor of Ansalon (d-3)

Emperor of Ansalon (d-3) The Messenger it-1

The Messenger it-1 The Druid Queen tdt-3

The Druid Queen tdt-3 Ironhelm mt-1

Ironhelm mt-1 The Dragons lh-6

The Dragons lh-6 The Last Thane cw-1

The Last Thane cw-1 Circle at center sc-1

Circle at center sc-1 Secret of Pax Tharkas dh-1

Secret of Pax Tharkas dh-1 Fistanadantilus Reborn ll-2

Fistanadantilus Reborn ll-2 Viperhand mt-2

Viperhand mt-2 Kagonesti lh-1

Kagonesti lh-1 The Druid Queen

The Druid Queen Lord of the Rose tros-1

Lord of the Rose tros-1 Goddess Worldweaver sc-3

Goddess Worldweaver sc-3 Eyeball to Eyeball (Final Failure)

Eyeball to Eyeball (Final Failure) Darkwell

Darkwell Fate of Thorbardin dh-3

Fate of Thorbardin dh-3 The Coral Kingdom tdt-2

The Coral Kingdom tdt-2 Wizard's Conclave

Wizard's Conclave The Coral Kingdom

The Coral Kingdom Winterheim it-3

Winterheim it-3 Emperor of Ansalon v-3

Emperor of Ansalon v-3 MacArthur's War: A Novel of the Invasion of Japan

MacArthur's War: A Novel of the Invasion of Japan The Fate of Thorbardin

The Fate of Thorbardin The Rod of Seven Parts

The Rod of Seven Parts Fistandantilus Reborn

Fistandantilus Reborn Prophet of Moonshae tdt-1

Prophet of Moonshae tdt-1 The Golden Orb i-2

The Golden Orb i-2