- Home

- Douglas Niles

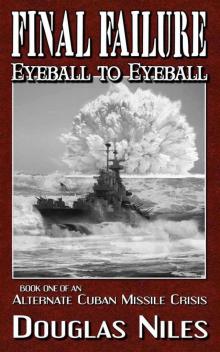

Eyeball to Eyeball (Final Failure)

Eyeball to Eyeball (Final Failure) Read online

Final Failure

Eyeball to Eyeball

Book 1 of an Alternate

Cuban Missile Crisis

by Douglas Niles

Copyright Ó 2012 by Douglas Niles

Cover Design: Katheryn Smith

Copyediting: Winifred Lewis

Typesetting: Ralph Faraday

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Requests for permission to make copies of any part of the work should be emailed to [email protected] or mailed to Popcorn Press at the address listed on www.PopcornPress.com.

Contents

Prologue: P-Hour

One: Operation Anadyr

Two: Mission 3101

Three: ExComm

Four: Countdown to Quarantine

Five: DEFCON 2

Six: Foxtrot B-59

Pre-Crisis Timeline

Author’s Note

Acknowledgements

Selected Bibliography

About the Author

“Now the question really is what action we take which lessens the chance of a nuclear exchange, which obviously is the final failure.”

President John Fitzgerald Kennedy

ExComm Meeting, 18 October 1962

White House, Washington D.C.

Final Failure is a five-book story of alternate history, set during a fictional Cuban Nuclear War of 1962. Some of the characters are actual historical figures, while others are the creations of the author. In each case, the narrative follows the conventions of historical fiction with regard to accurate portrayal of events…until a fictional incident on October 27, 1962, becomes the point of departure into alternate history.

In other words, this is a true tale of What Might Have Been.

For additional details, and updates regarding upcoming books in the Final Failure series, please visit douglasniles.com or facebook.com/AuthorDouglasNiles.

To Michael S. Dobson,

In sincere remembrance of all the history, both actual and “alternate,” we’ve shared over the years

Prologue: P-Hour

“Let every nation know…that we shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe, to assure the survival and the success of liberty.”

President John Fitzgerald Kennedy

Inaugural Address, 20 January 1961

22 October 1962

1852 hours EST (Monday Evening)

Oval Office, The White House

Washington D.C.

The Oval Office had been transformed into a reasonable approximation of a television studio. Sound and power cables snaked across the floor, which had been covered with a tarpaulin to protect the carpet. The massive wooden desk, constructed from timbers once part of the warship HMS Resolute, was now draped in black felt, with a backdrop of similar material, decorated only by the Presidential flag, hanging behind. Furniture was shunted aside to make room for multiple microphones, two cameras, recording equipment, and large banks of lights.

Now that all was ready, the technicians and publicity people withdrew. Attorney General Bobby Kennedy and the President’s secretary, Evelyn Lincoln, were the only people in the Oval Office as the President entered from the side door, walking stiffly as he approached his chair. With one hand propped on the corner of the desk, John Fitzgerald Kennedy limped to the seat and collapsed, wincing in pain.

His younger brother offered no reaction. Jack Kennedy’s back pain was a daily feature of his life, and the President resented any attempts at sympathy or what he described as coddling. Eventually, he would accept a shot or two of pain medication, but as the clock approached the moment that the administration had designated as P-Hour—7:00 PM on this crucial evening—such steroid and narcotic relief would have to wait.

The television cameras were already focused, hulking robots with glass eyes trained on the massive desk and the man sitting behind it. Bobby adjusted a pillow behind his brother’s back, helping him to sit straight in the chair.

“How’s that, Jack?” he asked. “Do you want another pillow? Should I move the chair back a bit?”

“No, it’s fine—thanks. Let’s get going,” the chief executive replied curtly.

Evelyn Lincoln reached a brush toward the President’s slightly mussed brown hair, but he waved her away and straightened it using his hand.

With a glance at the clock, JFK nodded his readiness.

“Better send them in,” he said.

Bobby went to the door and opened it, allowing Press Secretary Pierre Salinger to lead the cameramen and several sound and lighting technicians, all of them men dressed in suits, into the office. Each took up his station, the sound men kneeling before the black-draped platform as the bright lights came on one by one, washing the desk and its occupant in a bright arc of illumination. Bobby saw that Jack’s face was already composed, free of any evidence of pain. Instead, he looked stern, serious…Presidential.

With an eye on the clock, Salinger nodded at the President. “Alright, Sir. We’re on in ten seconds.” He paused, hand upraised, and counted down with his fingers.

“Three, two, one.”

John F. Kennedy stared squarely into the camera and began to speak, his familiar New England twang clipping each word with earnest intensity.

“Good evening, my fellow citizens.

“This government, as promised, has maintained the closest surveillance of the Soviet military buildup on the island of Cuba. Within the past week, unmistakable evidence has established the fact that a series of offensive missile sites is now in preparation on that imprisoned island. The purpose of these bases can be none other than to provide a nuclear strike capability against the Western Hemisphere.

“Upon receiving the first preliminary hard information of this nature last Tuesday morning at 9 A.M., I directed that our surveillance be stepped up. And having now confirmed and completed our evaluation of the evidence and our decision on a course of action, this government feels obliged to report this new crisis to you in fullest detail.”

1901 hours EST (Monday Evening)

Harry S. Truman Annex

Key West Naval Air Station

Key West, Florida

Commander Alex Widener stood on the tarmac just outside of the pilots’ ready room and watched the last of his F6A Skyrays, turbojet engine roaring as the afterburner spewed yellow flame, shoot down the runway. The powerful delta-wing fighter rose swiftly into the sunset shimmering over the Florida Strait.

At last: the base’s entire fighter squadron, twelve aircraft, was aloft. The mission was combat air patrol, or CAP. The Skyray was a high-speed fighter capable of aerial combat at altitudes of 50,000 feet or more. Patrolling in pairs, the dozen planes of Widener’s squadron already approached their stations, circling lazily, strung out along the Keys and ready to intercept any threat from the south.

And the commander knew that, for the first time in a long, long time, those pilots on the CAP mission faced the possibility of actual combat. Key West was the US territory closest to the island of Cuba, and Cuba had been the focus of an awful lot of American scrutiny over the last few months—scrutiny that had been immensely heightened in this past week. Widener, the base CO, was certain that the President’s speech tonight, the television address announced only earlier in the day, would deal with the crisis.

Having seen the last of his charges into the sky, the commander looked at the hangars and the still-crowded assembly areas on the tarmac. Key West had never

hosted so many planes, he knew: In addition to the fighter squadron, he’d been tasked with housing a squadron of RF8A Crusader low-range reconnaissance aircraft and a detachment of large, modern F4 Phantom fighters. He had just learned that a battery of Hawk antiaircraft missiles was on the way from Fort Meade, Maryland, and he been ordered to find space for a full Marine Air Group, fighters and ground-attack planes, that could be ordered here any day from California.

As he returned to the ready room, he was fully aware that something big was going on. Inside the steamy quonset hut, Chief Petty Officer Sullivan adjusted the rabbit ears on the little black-and-white television set, and by the time Widener had reached his desk, the picture was at least recognizable as the President. That Bostonian voice, flat and distinctive, was unmistakable even over the slight hiss of the feeble reception, and as he listened Widener immediately realized that things were every bit as serious as he had suspected.

“The characteristics of these new missile sites indicate two distinct types of installations,” Kennedy said. “Several of them include medium-range ballistic missiles, capable of carrying a nuclear warhead for a distance of more than 1,000 nautical miles. Each of these missiles, in short, is capable of striking Washington, D.C., the Panama Canal, Cape Canaveral, Mexico City, or any other city in the southeastern part of the United States, in Central America, or in the Caribbean area.”

The commander nodded his head in appreciation of the tactic. The President was making it clear that this was not just a problem for the United States, but a threat to the entire hemisphere. Widener had voted for Nixon in the ’60 election, and had been vocally skeptical of the young Democratic Chief Executive following the debacle at the Bay of Pigs—when JFK had refused to authorize the air and naval support that might have given the anti-Castro Cubans of the invasion force a chance at survival. But he could only approve of Kennedy’s resolute approach to the current situation.

He squinted as a picture, a photo reconnaissance shot with labels indicating various installations, replaced the President’s face on the screen. The picture was too fuzzy to make out the details, but he knew he was looking at a missile base on the island nation just ninety miles to the south.

“Additional sites not yet completed appear to be designed for intermediate-range ballistic missiles—capable of traveling more than twice as far—and thus capable of striking most of the major cities in the Western Hemisphere, ranging as far north as Hudson Bay, Canada, and as far south as Lima, Peru,” the President continued, ticking off facts like a prosecutor.

“In addition, jet bombers, capable of carrying nuclear weapons, are now being uncrated and assembled in Cuba, while the necessary air bases are being prepared.…”

1902 hours EST (Monday evening)

Newsroom

NBC Washington Bureau

Washington, D.C.

The reporters clustered around the large TV monitor and watched the address in uncharacteristic silence. Each was aware of history in the making. Each knew that this was a major story, and each mentally ticked off every source that might provide a unique vantage. Each journalist planned phone calls, envisioned interviews, thought about hypothetical assignments.

And each of them, but one, was a man.

Stella Widener didn’t take notes. The President’s address to the nation was being recorded right here in the newsroom, and she would consult the film record—probably many times—before writing her story. In fact, she had written the story, had pieced together the situation before anyone else at her network. But when she’d presented it to her news director just this morning, he’d order her to kill it—because of pressure from the White House. Now, she could only stare at the screen, at that handsome, grim face. She listened to the chilling words in a room that was otherwise silent until, finally, her cynical and worldly colleagues could no longer restrain the need to comment.

“Damn, I thought for sure it was going to be Berlin again,” one veteran newsman finally remarked, when JFK paused to take a breath.

“Nah, this year it’s all about Castro,” another replied knowingly. “And the Russians—this is some serious stuff.”

“Hey, Stella,” said a third. “Good thing you got out of Moscow when you did—they’d probably be sending you to a gulag if you hadn’t finished filming two months ago!”

The gallows humor got a good laugh, heartened by the professional jealousy these men felt for the woman who had scooped them all with the first American film footage shot inside the Kremlin. Since her return to D.C. in late September, Stella had endured a constant barrage of suggestive remarks as veteran newshounds badgered her about how she had gotten Khrushchev to allow her to film the documentary. They wouldn’t believe the truth—that it was good old-fashioned stubbornness and perseverance. She was a good reporter who relied on her skills and professional acumen to get the story.

But, she remembered, there was one dramatic exception. She flushed at a private memory: herself as a young reporter for the Boston Globe…a visit to a hotel suite to interview Massachusetts’ young, handsome, and recently married senator…the interview that had propelled her career to undreamed of heights…the closeness of that familiar voice, and face, that filled the television screen before her now.

“Shh!” she said impatiently, trying to hear the speech—and to will herself away from the guilty memory. The men complied, no doubt because they, too, were fascinated by the portentous address. The President looked tired, Stella thought, as JFK continued. And kind of angry, as well.

“This urgent transformation of Cuba into an important strategic base—by the presence of these large, long-range, and clearly offensive weapons of sudden mass destruction—constitutes an explicit threat to the peace and security of all the Americas, in flagrant and deliberate defiance of the Rio Pact of 1947, the traditions of this nation and hemisphere, the joint resolution of the 87th Congress, the Charter of the United Nations, and my own public warnings to the Soviets on September 4 and 13. This action also contradicts the repeated assurances of Soviet spokesmen, both publicly and privately delivered, that the arms buildup in Cuba would retain its original defensive character, and that the Soviet Union had no need or desire to station strategic missiles on the territory of any other nation.”

One reporter dashed to a typewriter at the back of the room, and seconds later the machine’s keys chattered loudly, a frantic cadence underlying the urgency of the speech. No one else tore himself away, at least not yet.

“Do you suppose it’s war?” someone mused rhetorically.

“No,” Stella replied. “He wouldn’t be announcing it like this if it was.” She couldn’t help thinking of her brother and father, and knew that if it came to war, they would both be on the front lines.

“The size of this undertaking makes clear that it has been planned for some months,” the President accused. “Yet, only last month, after I had made clear the distinction between any introduction of ground-to-ground missiles and the existence of defensive antiaircraft missiles, the Soviet Government publicly stated on September 11 that, and I quote, ‘the armaments and military equipment sent to Cuba are designed exclusively for defensive purposes,’ that there is, and I quote the Soviet Government, ‘there is no need for the Soviet Government to shift its weapons for a retaliatory blow to any other country, for instance Cuba,’ and that, and I quote their government, ‘the Soviet Union has so powerful rockets to carry these nuclear warheads that there is no need to search for sites for them beyond the boundaries of the Soviet Union.’

“That statement was false.”

1905 hours EST (Monday Evening)

Bachelor Officers’ Quarters

82nd Airborne Division

Fort Bragg, North Carolina

Second Lieutenant Greg Hartley was drunk, but not drunk enough. It seemed that the 82nd Airborne was going to war: all leaves cancelled for the entire unit, new orders coming down practically by the hour, a general stir of excitement permeating the ranks of officers and

men. Still, the division’s junior officers had been issued one last allotment of two beers apiece—just for today. Hartley had quickly consumed his own pair of Old Milwaukees, and since late afternoon had been buying bottles from his fellow officers. The going rate was $2.00 apiece.

In Hartley’s somewhat fog-shrouded mind, it had been a good use of $14.00. Now, however, although he had money in his wallet and thirst in his throat, the supply seemed to have dried up. Having struck out on his last pass through the hall, he staggered slightly as he entered the BOQ’s common room, standing behind a dozen or so other junior officers who all had their attention glued to the television set.

President Kennedy was talking. Hartley didn’t want to watch, or listen, but like a moth drawn to some horrible, consuming flame, he found himself paying attention to his Commander in Chief’s stark, frightening words.

“Only last Thursday, as evidence of this rapid offensive buildup was already in my hand, Soviet Foreign Minister Gromyko told me in my office that he was instructed to make it clear once again, as he said his government had already done, that Soviet assistance to Cuba, and I quote, ‘pursued solely the purpose of contributing to the defense capabilities of Cuba,’ that, and I quote him, ‘training by Soviet specialists of Cuban nationals in handling defensive armaments was by no means offensive, and if it were otherwise,’ Mr. Gromyko went on, ‘the Soviet Government would never become involved in rendering such assistance.’

Feathered Dragon mt-3

Feathered Dragon mt-3 The Kinslayer Wars

The Kinslayer Wars Black Wizards

Black Wizards The Heir of Kayolin dh-2

The Heir of Kayolin dh-2 The Crown and the Sword tros-2

The Crown and the Sword tros-2 Realms of Valor a-1

Realms of Valor a-1 Wizards Conclave aom-5

Wizards Conclave aom-5 Fox On The Rhine

Fox On The Rhine The Heir of Kayolin

The Heir of Kayolin Fox at the Front (Fox on the Rhine)

Fox at the Front (Fox on the Rhine) Measure and the Truth tros-3

Measure and the Truth tros-3 Emperor of Ansalon (d-3)

Emperor of Ansalon (d-3) The Messenger it-1

The Messenger it-1 The Druid Queen tdt-3

The Druid Queen tdt-3 Ironhelm mt-1

Ironhelm mt-1 The Dragons lh-6

The Dragons lh-6 The Last Thane cw-1

The Last Thane cw-1 Circle at center sc-1

Circle at center sc-1 Secret of Pax Tharkas dh-1

Secret of Pax Tharkas dh-1 Fistanadantilus Reborn ll-2

Fistanadantilus Reborn ll-2 Viperhand mt-2

Viperhand mt-2 Kagonesti lh-1

Kagonesti lh-1 The Druid Queen

The Druid Queen Lord of the Rose tros-1

Lord of the Rose tros-1 Goddess Worldweaver sc-3

Goddess Worldweaver sc-3 Eyeball to Eyeball (Final Failure)

Eyeball to Eyeball (Final Failure) Darkwell

Darkwell Fate of Thorbardin dh-3

Fate of Thorbardin dh-3 The Coral Kingdom tdt-2

The Coral Kingdom tdt-2 Wizard's Conclave

Wizard's Conclave The Coral Kingdom

The Coral Kingdom Winterheim it-3

Winterheim it-3 Emperor of Ansalon v-3

Emperor of Ansalon v-3 MacArthur's War: A Novel of the Invasion of Japan

MacArthur's War: A Novel of the Invasion of Japan The Fate of Thorbardin

The Fate of Thorbardin The Rod of Seven Parts

The Rod of Seven Parts Fistandantilus Reborn

Fistandantilus Reborn Prophet of Moonshae tdt-1

Prophet of Moonshae tdt-1 The Golden Orb i-2

The Golden Orb i-2