- Home

- Douglas Niles

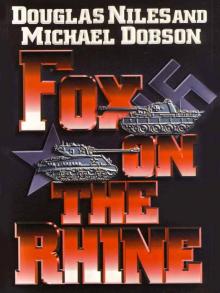

Fox On The Rhine

Fox On The Rhine Read online

FOX ON THE RHINE

Douglas Niles and Michael Dobson

Copyright © 2000 by Douglas Niles and Michael Dobson

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book, or portions thereof, in any form.

A Forge Book

Published by Torn Doherty Associates, TOR COM

ISBN: 0-812-57466-4

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 00-27675

First edition: June 2000

First mass market edition: June 2002

This book is respectfully dedicated to our fathers, Donald Niles, Sr., and Odell F. Dobson

This is a novel of alternate history, in which a historical event is changed, as are the consequences of that event along with it. Historical characters are portrayed in a fictional way; all their actions, words, thoughts, and behavior on or after 12:42 Berlin time (11:42 Greenwich Mean Time) on July 20, 1944, are solely the authors’ invention. Furthermore, invented characters in this book are fictitious. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead is purely coincidental. Details of the actual historical event and other background material can be found in the appendixes to this book.

Lieb Vaterland, magst ruhig sein,

Fest steht und treu die Wacht am Rhein!

--Die Wacht am Rhein, 1840 (a patriotic song)

"Dear fatherland, may you be steady, stand firm and true and guard the Rhine!”

PROLOGUE

July 17, 1944

Livarot-Vimoutiers Road, Normandy, France, 17 July 1944,1817 hours Greenwich Mean Time (GMT)

Every day, Field Marshall Erwin Rommel toured the front. The inspections seemed increasingly futile, but remained his duty nonetheless. His duty to the men of his command now overshadowed his duty to those above him, those who had betrayed his men, ignored his plans, hesitated at crucial moments, divided scarce resources, issued ludicrous orders, and enabled the Allies to secure a beachhead on the bloody shores of Normandy. Once he had thought the obstructions came from petty people in the shadow of the führer, but now he knew they came from the führer himself. The Desert Fox knew he could have stopped the Allied invasion, turned the American and British armies back, or at the very least delayed them, but his hands had been tied. And now the Allies were here to stay.

The campaign was futile, but still the battle raged on. Rommel’s army fought tenaciously, because of the oath he had taken, the oath his men had taken, the oath to which they all subscribed. He knew the war must be ended, and ended now--he’d even spoken quietly to other officers about how it would be better to live as a British dominion than see Germany ruined. But as long as Adolf Hitler lived, the Fatherland faced a future of inevitable destruction.

The field marshal had exchanged brusque words with Hitler only days before. Rommel had been outraged by the massacre at Oradour-sur-Glade, in which the SS division Das Reich had killed more than six hundred men, women, and children in reprisal for the killing of a German officer in Oradour. But the SS had picked the wrong Oradour--there were two of them. “Such things bring disgrace on the German uniform,” he told the führer. “How can you wonder at the strength of the French Resistance when the SS drive every decent Frenchman into joining it?”

Field Marshal von Runstedt, the supreme commander, had appeared shocked at the outburst, though Rommel suspected that Runstedt, like so many of the old aristocracy, was secretly in sympathy with him. Both field marshals had been giving subtle hints about making overtures to the western Allies, but Hitler would have none of it.

“That has nothing to do with you. It is outside your area. Your business is to resist the invasion “

Now the field marshal shook his head in disgust, and to clear the thoughts from it. “What is the matter, Herr Feldmarschall?” asked Captain Lang, riding in the backseat of the staff car.

“Nothing, nothing,” the Desert Fox replied irritably. This day they had toured the 276th and 277th Infantry Divisions, which had repulsed a heavy enemy attack the night before. Then he had endured a frustrating meeting with General Sepp Dietrich at the Second SS Armored Corps. They had left the meeting around four o’clock because he was anxious to get back to Army Group B headquarters, where he would attempt to deal with yet another enemy breakthrough on yet another part of the front.

The SS divisions, a separate military structure, were a particular irritation. When Rommel commanded in northern Italy, he had faced continual trouble from General Dietrich. The field marshal had finally ordered the SS units out of Milan, out of his area. They were not honorable soldiers. They did not obey orders. They looted and brutalized in ways that fell outside the pale.

A thunderous concussion rocked the air--another Allied bomb. “They’re rather heavy today,” observed Lang diffidently.

The field marshal turned to look at him. His famous temper began to boil up; he admired physical courage and stoicism and disliked its obverse. But he calmed at once. “Yes, they are,” he replied mildly. For the unchallenged Allied air superiority was one of the obstacles that even the great field marshal’s tactical and strategic skills could not overcome. He could not blame Lang for feeling helpless in the face of Allied fighter bombers, the hated Jabos, for he did himself.

He looked out the window as they passed one more burning truck, yellow flames still licking the shreds of canvas cover. In the distance a great plume of black smoke smudged the sky over the main highway. No doubt the pyre marked the death of an entire convoy of his precious vehicles, men, and supplies.

Sergeant Holke, the spotter, binoculars pressed to his eyes, shouted from the back. “They’ve seen us--two are coming this way.”

A different man would have cursed, but the field marshal merely tightened his fists and ordered Corporal Daniel to make haste. The driver pressed the accelerator, and the big staff car surged forward. “There is a crossing ahead, Herr Feldmarschall,” called Daniel, without taking his attention from the road.

“Turn off there,” said the field marshal. “At least we’ll have a little shelter.”

If they could only reach the side road in time, they could likely dash away before the speeding aircraft turned to pursue. Twisting in his seat, Rommel looked to the rear, his keen eyes spotting the first of the enemy planes. The aircraft followed the line of the road, coming up very fast behind them, startlingly close to the ground.

He knew they would never make the crossroads.

Tracers flashed and dust rose from the gravel right behind the car. A moment later metal and glass splintered with terrible violence. The field marshal lost consciousness as a punishing blow crushed the socket of his left eye and broke bones in his cheek and skull. He felt nothing as the grievously wounded driver convulsed at the wheel, steering the car violently into a tree.

The vehicle spun back across the road, bounced off a wall, and rolled over to land on its top in the ditch. The field marshal lay on the ground, blood flowing from his eyes, nose, and mouth. Overhead, the second tactical fighter roared in, more guns firing. At the last minute the pilot released a small fragmentation bomb, plunging the deadly missile into the carnage below.

An hour later, a French doctor pronounced the Desert Fox a hopeless case. He was put in a hospital bed to die, while in the rest of Normandy, in Germany, and throughout the world, the greatest of all wars raged upon its relentless course.

OPERATION VALKYRIE

July 20, 1944

Wolfschanze, East Prussia, 20 July 1944, 1132 hours GMT

The sharp-featured Prussian field marshal approached Hitler’s headquarters bunker, trailed by several staff officers. The SS hauptmann standing guard at the door snapped his arm upward in a salute and shouted as a heavy cement truck rolled by.

“Field Marsh

al Keitel. Der führer is expecting you. Since they are reinforcing the command bunker, the conference will be held in Minister Speer’s barracks.”

“Very well,” the aristocratic commander replied. His face was etched with deep lines, and black circles darkened the skin around his eyes. Keitel turned to one of his accompanying officers and glanced down at the man’s solid briefcase. “Did you bring the information on the Replacement Army?”

Colonel Count Claus Schenk von Stauffenberg instantly tightened his grip on the satchel’s handle. He stood stiffly, nearly as tall as the field marshal, and was every bit his equal as an aristocrat if not in military rank. Von Stauffenberg was a soldier who had suffered grievously for the Reich. A black patch covered his left eye, and his sleeve on the same side was pinched shut at the wrist, hanging empty beside his Wehrmacht colonel’s tunic. He clasped his large briefcase in his right hand, even though he had lost fingers there to the same explosion that had claimed his arm and his eye. “Jawohl,” he replied, indicating the briefcase with a nod. (He was sweating for reasons other than the oppressive heat.)

The colonel glanced over at the footings for the new large command bunker, a symptom of the Soviet advance. A foreman was yelling at his crew; as always, Wolfschanze, the “Wolf’s Lair,” was a beehive of construction activity, with new fortifications being thrown up while the war moved closer and closer.

Keitel noticed Stauffenberg looking at the new command bunker. “The tide will yet turn in our direction,” the field marshal observed.

Stauffenberg looked at his commander. “Yes, Field Marshal,” he replied. “And perhaps sooner than we think.” His face was carefully expressionless, giving away nothing of his true thoughts. Only the beads of moisture on his forehead betrayed his tension, and those could easily be explained by the heat. He knew Keitel was still loyal to the führer and would be until the end--which would come sooner than the field marshal could possibly imagine.

Minutes before, Stauffenberg had opened the briefcase and reached inside to crush a glass ampule. The subsequent chemical reaction had activated a fuse. By the colonel’s estimate, the bomb in the briefcase would go off in about ten minutes. If all went well, by the end of the day Germany would begin to emerge from the long night of dictatorship and fascism.

Keitel merely nodded, obviously pleased at the patriotic response, as he led his staff toward the barracks. Twice, staff officers offered to carry Stauffenberg’s briefcase, but each time he refused the help. The seconds crept slowly by as they approached the Speer Barracks. This was one of the old wooden structures, built before fortifications at the Wolf’s Lair were deemed necessary. The building looked like a long one-story lodge in the woods, not at all like a sophisticated field headquarters for the mighty military machine that was the Third Reich.

To von Stauffenberg, the change raised a pragmatic concern. He worried that his bomb might not be sufficient for the job, that the open windows would diffuse the blast and reduce the damage it would cause. He suppressed a grimace. Why had Keitel interrupted him before he could get the second bomb from Haeften? But there was nothing to be done about that now.

Inside the conference room more than a dozen uniformed officers stood about in various states of unease, while an equal number of stenographers scribbled their notes at writing tables placed haphazardly around the perimeter of the conference bunker. A broad map table filled the center of the room, and the short, dark-haired figure of the führer bent over those sheets, his shoulders and arms tight with barely-concealed tension. He looked up, piercing eyes flashing angrily, as Keitel and Stauffenberg entered.

General Adolf Heusinger was clearly trying to complete his briefing without provoking another Hitler outburst. “The attempts to reform Army Group Center are being met with some..., er, limited success. Zhukov’s armies continue to advance, however. Three days ago some elements of the First Guards Tank Army crossed the Bug River into Poland--although the defenders of Lvov stand heroically firm. In the north, I regret to report, there is a real possibility that Stalin’s horde will reach the Baltic. In that case, our armies in Latvia and Estonia will be lost... unless... or rather, if, they were to make a strategic movement toward the Fatherland--”

“The German army will never withdraw! It will fight and be victorious--or it will die! But it will never retreat” He was sweating for reasons other than the oppressive heat. Hitler’s voice rose nearly to a shriek, his eyes fastened on the quivering lieutenant general. “How is it that you cowards in the Wehrmacht can’t get that fact through your thick heads? Proceed--but do not mention withdrawal!”

“Jawohl, mein Führer!” Heusinger gulped and mopped his brow, then continued with the dolorous report, trying unsuccessfully to highlight the rare bits of positive news.

Stauffenberg felt some sympathy for the man, knowing that the task of sugarcoating the news was virtually impossible. In truth, Army Group Center--the greatest concentration of men and materiel ever gathered under German command--had been virtually obliterated by the massive Soviet spring offensive.

About the best the hapless Heusinger could do was dangle the hope that the sweeping Soviet advance must surely be carrying the Russian tanks far beyond their bases of supply. Also, he emphasized, the bridgehead across the Bug was still small. Of course, none of the unspoken realities would escape any of the experienced army officers here, but these professional soldiers knew to a man that it was nothing short of suicide to confront the führer with truths he did not wish to hear.

Stauffenberg stepped up to the table as Field Marshal Keitel moved to Hitler’s side. The colonel had asked Major von Freyend to find him a place close to Hitler to compensate for his poor hearing, and von Freyend was happy to oblige. Stauffenberg’s one good eye never blinked as it appeared to consider every detail on the wide map, with its huge expanse of flags and colored lines, the sweeping horde beneath the hammer and sickle closing onto the heart of the Reich. His heart pounded, and anger and despair writhed together as he observed this graphic depiction of national catastrophe. So this is the end to which the führer would lead us. Well, today, right here, the madness stops.

The colonel carefully set his heavy briefcase down underneath the table. Months of stealth, of plotting, of careful recruiting had led to this moment. The explosion would kill most of the people in the barracks, he knew, and not all of them deserved to die, but then so many people had not deserved to die. These deaths, at least, would bring the insanity to an end.

“Herr Oberst--there is a call for you, from Berlin.” Stauffenberg turned to see a messenger whispering at his side. “General Fellgiebel said it was urgent.” Nodding silently, the crippled officer took one last look at Adolf Hitler, führer of the Third Reich, and smiled his tight smile before following the messenger from the conference hut, moving quickly across the compound toward the communications building, following the cue of his coconspirator. He completely forgot his cap and gunbelt.

He didn’t forget his briefcase. It remained exactly where he wanted it, under the table, a few feet from the führer’s legs.

Colonel Heinz Brandt moved into the space at the table vacated by Stauffenberg. Brandt, an aide to General Heusinger, was an operations officer on the general staff. He was pondering a disturbing bit of news. Unconfirmed reports from the Balkans had been coming into the OKW headquarters, indicating the possibility of defection by Rumania and Bulgaria. The two nations had never been enthusiastic participants in the epic war against the USSR, and now that the eastern hordes rolled toward them, Brandt’s sources indicated that either or both countries might be preparing to change sides.

Yet how could he bring this up to the führer? Brandt’s idealism and patriotism had been sorely tried these past months. He still revered his führer, but those bursts of temper were coming more and more frequently. And too often they meant disgrace or disaster to the recipient.

His position at the table was awkward, and he realized that his foot was blocked by Stauffenberg’s briefcase. He r

eached down to move the leather satchel to his right, finding that it was surprisingly heavy. As he started to shove it behind the thick stanchion supporting the table, however, he was possessed by the sudden urge to sneeze. He froze, embarrassed by his awkward stance, tense because of his proximity to Hitler. Struggling to suppress the tickle in his nose--a distraction such as a sneeze, however involuntary, always irritated the führer--Brandt decided that the briefcase could remain where it was. He straightened with careful dignity, ignoring the damnably heavy satchel, relieved that he managed to keep from attracting unwanted attention to himself.

More ominous facts and figures mounted up: the Americans and British continued to reinforce their beachhead in Normandy, which was now six weeks old. The German defenders held their positions with heroic courage, but the Wehrmacht commander in the west, Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, had just been critically injured by an Allied air attack. The report sent by his replacement, von Kluge, indicated that his troops were stretched to the breaking point, that the defensive shell must soon crack.

Meanwhile the heavy bombers kept coming, day and night, raining death on Germany’s cities and destruction upon the Third Reich’s industrial capabilities. Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring’s representative reluctantly admitted that the Luftwaffe was horribly depleted, critically short of spare parts, barely able to scrape together enough fighters to harass the thundering fleets of enemy bombers.

Hitler’s eyes again flashed. “And the rigging of the jet bombers? How fares that?”

The unfortunate Luftwaffe officer paused awkwardly. Like every other former combat pilot, he undoubtedly realized the potential of the rocket-fast plane designed by Willy Messerschmidt--the Me-262. Certainly it was glaringly obvious to him, and to everyone else in the Luftwaffe, that the short-ranged aircraft would make a magnificent fighter. Still, Hitler felt a passionate need to strike back at the enemy homeland in revenge for the bombing of Germany, and to that end he had insisted that the aircraft be rigged to carry bombs--a task for which the plane was patently unfit. Thus, the development of a premier weapon had been placed indefinitely on hold. Brandt, an army man more familiar with diplomacy than air power, nevertheless felt sympathy for the flying officer who was now forced to confront his ruler’s irrationality.

Feathered Dragon mt-3

Feathered Dragon mt-3 The Kinslayer Wars

The Kinslayer Wars Black Wizards

Black Wizards The Heir of Kayolin dh-2

The Heir of Kayolin dh-2 The Crown and the Sword tros-2

The Crown and the Sword tros-2 Realms of Valor a-1

Realms of Valor a-1 Wizards Conclave aom-5

Wizards Conclave aom-5 Fox On The Rhine

Fox On The Rhine The Heir of Kayolin

The Heir of Kayolin Fox at the Front (Fox on the Rhine)

Fox at the Front (Fox on the Rhine) Measure and the Truth tros-3

Measure and the Truth tros-3 Emperor of Ansalon (d-3)

Emperor of Ansalon (d-3) The Messenger it-1

The Messenger it-1 The Druid Queen tdt-3

The Druid Queen tdt-3 Ironhelm mt-1

Ironhelm mt-1 The Dragons lh-6

The Dragons lh-6 The Last Thane cw-1

The Last Thane cw-1 Circle at center sc-1

Circle at center sc-1 Secret of Pax Tharkas dh-1

Secret of Pax Tharkas dh-1 Fistanadantilus Reborn ll-2

Fistanadantilus Reborn ll-2 Viperhand mt-2

Viperhand mt-2 Kagonesti lh-1

Kagonesti lh-1 The Druid Queen

The Druid Queen Lord of the Rose tros-1

Lord of the Rose tros-1 Goddess Worldweaver sc-3

Goddess Worldweaver sc-3 Eyeball to Eyeball (Final Failure)

Eyeball to Eyeball (Final Failure) Darkwell

Darkwell Fate of Thorbardin dh-3

Fate of Thorbardin dh-3 The Coral Kingdom tdt-2

The Coral Kingdom tdt-2 Wizard's Conclave

Wizard's Conclave The Coral Kingdom

The Coral Kingdom Winterheim it-3

Winterheim it-3 Emperor of Ansalon v-3

Emperor of Ansalon v-3 MacArthur's War: A Novel of the Invasion of Japan

MacArthur's War: A Novel of the Invasion of Japan The Fate of Thorbardin

The Fate of Thorbardin The Rod of Seven Parts

The Rod of Seven Parts Fistandantilus Reborn

Fistandantilus Reborn Prophet of Moonshae tdt-1

Prophet of Moonshae tdt-1 The Golden Orb i-2

The Golden Orb i-2