- Home

- Douglas Niles

Fox On The Rhine Page 3

Fox On The Rhine Read online

Page 3

Old equipment and not much of that, he thought. Control of the air, he knew, was critical to turning the tide of battle. We are still Germans. We are still supreme. If we have the will as a people, we cannot be stopped.

He throttled back as his plane descended toward the dirt landing strip. He could see people waving, the colonel striding angrily over to him to berate him for disobeying orders. But Krueger was not worried. The colonel tended to back off when Krueger was truly angry. And if this time he didn’t, well, Krueger had totaled up the numbers. With the two downed aircraft today, he’d scored his 150th kill.

Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Forces (SHAEF), London, England, 1215 GMT

General Omar Bradley, commander of the United States First Army, nodded to the secretary outside the supreme Allied commander’s door. “Go right in, General,” she said. “He’s ready for you.”

Dwight D. Eisenhower, five-star general, put down his half-eaten sandwich and smiled. “Welcome back to England, Brad,” he said, standing up and offering his hand.

“Thanks, Ike,” Bradley replied. “Sorry to interrupt your lunch. I’m just passing through, though. I go back across the Channel tomorrow.”

“I’ll be over there soon enough myself,” Eisenhower said. “But there’s all this to get through first--” he indicated a maze of paper. “I’ve been in so many meetings lately that my keister is qualified for the Purple Heart.”

Bradley laughed and settled into a chair.

“So what’s new that isn’t already in these reports?” Eisenhower asked. He had often voiced his frustration to Bradley about being shut off from firsthand experience so much of the time; he had to put together his knowledge from other people’s accounts to make sense of the myriad reports that piled up before him. And there were few people he trusted as much as Omar Bradley, who had been a classmate of Eisenhower’s at West Point.

“We’re opening the Cherbourg port tomorrow; all the German demolition damage is just about corrected. That means we’ll be able to bring in tanks and troops through a regular port and not through the artificial ports. Monty’s got his hands full with German armor but keeps talking about a breakthrough. At least we’re getting more troops and more equipment across every day, and that’s going very well.” Bradley’s quiet and calm demeanor was a contrast to the often bombastic and too frequently self-serving or political rhetoric Eisenhower got from his other generals. Especially his two chief prima donnas--Monty, the British field marshal Bernard Montgomery, who had been commander of ground forces in the D-Day landings, and General George Patton, the brilliant but egotistical tank commander who had been sidelined during D-Day in a huge and successful bluff to convince the Germans that the attack would come elsewhere than Normandy.

“We’re making progress, Ike. Not as fast as we’d like, of course, but we’ve rocked the Krauts back on their heels along the whole line. It’s a hell of an accomplishment since D-Day.” Eisenhower nodded in grim agreement. The risk and the carnage of the D-Day landings--only six weeks past!--was still fresh in everyone’s mind. The situation on the ground in Normandy was much more fluid and dangerous than the Allied command wanted.

“And Operation Cobra?” asked the supreme commander, referring to the military plan for the Allied breakout from the Normandy peninsula into France.

“On track. We’ll start the final briefing soon. With luck, Cobra should get us out of those damned hedgerows and heading through France.”

“There’s a long road ahead of us still,” Eisenhower observed.

Bradley nodded. “But we’ll win. There’s no doubt left, really.” Coming from the imperturbable Bradley, the statement was unassailable.

“Did you hear about Rommel?” Eisenhower asked. “Three days ago he got shot up by a British fighter--Canadian, excuse me. We thought he was dead, but he’s in the hospital. Pretty badly wounded, by all accounts. Looks like his war is over.”

Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, the famous Desert Fox who had fought so brilliantly in North Africa, had commanded the defense of the D-Day beaches, in places nearly driving the Allies back into the sea. In the end it might have been only Hitler’s refusal to believe that the Normandy invasion was real that had saved the attack. The führer had refused to allow Rommel to counterattack with his panzer divisions, forcing the German tanks out of action until the Allies had a secure foothold on the shore.

“It’s good we don’t have to fight him any more in Normandy,” Bradley mused.

“Well, I wanted another crack at the son of a bitch!” The voice of George Patton, his characteristically high-pitched squeak, came from the office door as the general strode into the room.

“George,” Bradley acknowledged, standing to shake Patton’s hand. He noted that even here he wore his twin ivory-handled revolvers in their belt holsters. Despite his voice, the general, in his immaculate tunic and shiny cavalry boots, demanded respect, even from his superior officers. Bradley studied him, wondering where Patton’s volatile personality was going to take them today.

“So, Ike, Brad?” Patton said with easy familiarity, though he made no move to join Bradley in sitting down. “When do I get my army?”

Bradley grimaced while Eisenhower chuckled. The supreme commander indicated his field commander. “You want to tell him, Brad?”

“I wouldn’t be taking anything for granted if I were you,” Bradley snapped. “But yes, we’re going to activate Third Army. It looks like you’ll take over about the first of August--if you don’t make an ass out of yourself before then.” Once personally close--Patton had been Bradley’s commanding officer--the two had an increasingly tendentious relationship.

For a second the bombastic front fell away and Patton grinned like an enthusiastic child. Then he was serious again. “You won’t regret this, either of you. Just turn me loose over there! And I don’t care if it’s Rommel or Old Scratch himself on the other side!”

Eisenhower nodded, satisfied. “Though now it looks like von Kluge is in charge of the front.” He turned back to Bradley. “Does that make any real change in your plans?”

“Not really. Kluge is competent; hell, they all are. But he’s going to have to deal with Hitler and all kinds of directives that are going to mess up any smart strategy. The Germans are going to be troublesome all through France, but I don’t think they’ll be able to do much once we break out all the way, at least until we hit the German border.”

“I agree. Sometimes I think Hitler’s one of the best military allies we’ve got. He’s tying the hands of his generals in ways we can only dream about.” The three men laughed. “So, Brad, you’ve got your new units in place?”

Bradley stole a look at Patton and wished that the army commander wasn’t here, not right now. But he went ahead anyway.

“Just wanted to review the final status of the Nineteenth Armored Division, which I’m activating and shipping over this week. I’ve got Jack King in command with Henry Wakefield as his executive officer.”

“King’s aggressive as hell. George, you’ll like him. But you’re pairing him with Henry Wakefield?” Eisenhower put his hand on his chin. “So, Henry finally got away from training commands, hmm?” The supreme commander himself had been a tank instructor, with Henry Wakefield as a contemporary.

“Yep,” replied Bradley, with another glance at the scowling Patton. “You know why he didn’t go to Africa or Italy.” Eisenhower nodded. He remembered the pivotal meeting at the Command and General Staff College, where Henry Wakefield and George Patton had butted heads. It was loud and explosive. The doctrinal points were important, though perhaps not as crucial as the two men believed--Patton tended to believe anyone who didn’t see the future of armor the way he did was a blind idiot, and Wakefield had his own insights into tank warfare. When Patton became operational commander in North Africa, any chance Wakefield had of getting an armored command of his own evaporated. But now that the Allies had landed in Europe, there was too much need.

“I guess y

ou have in mind that Henry will keep Jack from getting too far ahead of himself,” Ike mused.

“That’s right,” replied Bradley. “And Henry deserves a chance. He’s a good man; he just came out on the losing end of a headquarters fight.”

Patton couldn’t keep quiet “You ask me, he doesn’t belong on a battlefield.”

“George, I didn’t ask you!”

“Well, I’m--”

Eisenhower cut them off. “Listen, George, let me finish up with Brad. I’ll see you at the map in the situation room--ten minutes.”

“Yessir!” Patton agreed, once again relaxing into that boyish grin. He turned and stalked out the door, and Bradley could easily imagine the clerks and secretaries scattering out of his path. He turned back to Eisenhower as the supreme commander spoke again.

“Who’s Jack got to head up his combat commands?”

‘Two colonels, both blooded. Colonel Bob Jackson ... and Colonel James Pulaski.”

Eisenhower’s eyebrows rose. Bradley knew he considered Jackson to be a good and stable choice. “Pulaski?”

“I know, Eke. He’s a Patton man through and through, and he’s a hothead to boot. You know and I know that his Silver Star is partly for luck, but luck isn’t such a bad characteristic for a tank leader. And I think this is a good assignment. He’ll get along well with King, and with any luck, Wakefield will pound a little sense into his head in the process.”

Bradley was familiar with the young officer’s being sound. In the North Africa campaign, Pulaski, then a newly-minted major, had led five tanks into what turned out to be a German trap, but then had fought his way out with the loss of only one of his own tanks, while crippling four panzers, and had been awarded the Silver Star. Eisenhower had groused about the stupidity of getting trapped in the first place, but then the handsome young officer had gotten his picture in the paper and become a brief celebrity. Patton liked him, and he’d been made a major.

A minor wound had returned him Stateside for a few months. Then he’d struggled to get back into the war, but Patton’s assignment to run the semi-imaginary First U. S. Army Group, the bluff operation to make the Germans believe the invasion was coming into Pas de Calais, had made him unable to support his erstwhile protégé. This was Pulaski’s chance to return as a freshly made colonel.

Eisenhower shook his head. “Brad, this is your show. I hope to hell you know what you’re doing, mixing fire and gasoline like that.”

“If it works, that mixture will get a lot done,” Bradley said. “If it works,” emphasized Eisenhower. “So, what other surprises can we expect?”

“With Hitler, who can tell?” replied Bradley.

Templehof Airport, Berlin, Germany, 1340 hours GMT

The speedy twin-engine Heinkel He-111 bomber descended toward the runway from the west, providing its two passengers with a splendid view of the German capital. The plane was far faster than the lumbering Junkers Ju-52 transport plane that had brought the conspirators to their fateful meeting with Hitler. “The capital of a new Germany,” Colonel von Stauffenberg shouted over the engines. “A Germany without Hitler, free from its Nazi masters!”

Lieutenant Werner von Haeften, the colonel’s aide, was fidgeting in visible agitation. It wasn’t done yet, not nearly, and he was still coming to grips with the irrevocable enormity of their action. Although a loyal member of the conspiracy--he had carried the second bomb, in case it had been needed--it was hard for him to grasp that the deed had actually been done. A Germany without the führer was a truly alien concept. He felt as if he’d killed a deity, a national father figure. Was he a parricide or a hero? Or both?

As the bomber taxied to a halt, he followed Stauffenberg to the waiting staff car and settled in the back.

“Bendlerstrasse, and quickly,” Stauffenberg commanded the driver. As the staff car raced toward the War Ministry building, he let some of the tension in his face relax.

“Now the difficult work begins,” Stauffenberg said with a dangerous smile.

Haeften knew he was being teased for his obvious nervousness. “And what would you call what we have just done?” “Merely a prelude, my dear Werner,” the colonel said. “There

is so much more to accomplish, and so little time. Operation Valkyrie must be turned into a reality. General Olbricht has approached General Fromm to put his influence and the power of the Replacement Army behind the coup. The reserve force should have--must have--begun to muster by now. We have a lot of work to do--Himmler needs to be neutralized, and Göring eased into command so that he can negotiate a surrender. We have accomplished the beginning, but our comrades in the conspiracy also have important roles to play.”

Haeften had joined the plotters early, in those difficult and dangerous days in which even the attempt to sound out officers to find those who might be sympathetic could easily lead to betrayal, torture, and death. Years of plotting, including two failed attempts on Hitler just this month--and only now coming to fruition. “But the führer is dead!” he said triumphantly.

Stauffenberg smiled. “Finally, after all these years, it seems almost too good to be true. The fuse worked soundlessly, just as our British friends had promised.”

Nearly running through the doors of the huge War Ministry, building in Bendlerstrasse, where Stauffenberg served as chief of staff to General Fromm, the two successful plotters entered Stauffenberg’s office. It was crowded with the gathering conspirators, men sitting and smoking, or pacing anxiously. Stauffenberg was first struck with the lack of action, the lack of initiative among his fellow conspirators. It gave him an immediate pang of concern.

“Claus--thank God you’ve made it back!” Olbricht was the first to speak, rising to his feet and clasping the count’s hand warmly.

“Success!” cried Stauffenberg. “He’s dead! Now, how fares the coup?”

He noticed Beck, then, looking vaguely out of place in his uniform--the uniform he had not worn in six years. The old officer, venerable survivor of the pre-Hitler general staff, who had

resigned in protest against Hitler’s plans to invade Czechoslovakia, clasped Stauffenberg’s hand warmly. Beck’s face was flushed, his eyes watering. He was obviously moved, and more than a little disturbed, by the actions of the men in this room.

Gradually the colonel realized that no one had answered his question. “The telephones?” He gestured to the dozen or so instruments in the room, none of which were in use. “Have you put through the calls to Vienna ... Munich? Has Stulpnagel acted in Paris?”

“We--we wanted to make sure, to hear from you yourself,” General Olbricht explained, somewhat sheepishly. Though he outranked the colonel, his manner clearly indicated who the conspirators valued as leader. “The message came--Die Brucke ist Verbrennt--but we wanted to make sure it wasn’t some kind of trick.”

Precious minutes wasted. Damn it! Stauffenberg flared with anger. How can they just sit there like that? “It’s no trick! He’s dead, I tell you! Quickly, to the phones--spread the word! Where’s Fromm--will he go along with us?”

Again there came that awkward silence. “He--he wouldn’t command the Replacement Army to revolt,” Olbricht explained again. “I’m afraid we’ve shuttled him into a closet.”

“What about Remer? Has the Ninth Regiment surrounded the Ministry of Propaganda?”

“Oh, yes,” Olbricht said, obviously relieved at having good news. “Yes, he is awaiting further orders. And, by the way, I’m ready to initiate command of Operation Valkyrie.”

“But surely that operation has already begun?” the count demanded, increasingly frustrated. One could not select one’s coup partners, he realized, nor simply court-martial or transfer them if they did not work out. Years of subservience to Hitler had made lapdogs out of many of the generals. He supposed he should not be surprised at their lack of initiative now, when it was needed most.

Olbricht nearly stammered in his eagerness to justify himself. “Of course--well, the orders are prepared, in any event. We wer

en’t sure whether to send them in clear or encode them.”

In other words, you have done nothing, he thought, but forced aside his frustration to consider the question. A clear message would be received almost immediately by all units of the Wehrmacht--but also by the many listening posts of the Allies. He recalled the ominous words of Roosevelt--unconditional surrender. Would they take advantage of the chaos to launch attacks? Almost assuredly.

“Send the announcement in code!” he declared, deciding that the extra time required for individual copies, for decoding, would be worth the added security.

Only later would he realize the enormity of his mistake.

Normandy, France, 1345 hours GMT

The sight of the D-Day beaches shocked any potential comment right out of Colonel James Pulaski’s vocabulary. As the flat-bottomed tank transport churned toward Utah Beach, he was stunned to silence by the swath of rusting carcasses scattered across the shallows and the flat landscape beyond. Unconsciously he touched the silver crucifix he wore just below his throat, and he wondered at the savagery that had rocked this coast.

Mangled LCTs rested on the shoals, while the burned-out hulks of several tanks settled into the soft sand to form a strange sort of sculpture, as exotic and memorable in its size as Stonehenge, or the heads of Easter Island. Burial details had long since cleared the beaches of the thousands of bodies, but the machinery stood like statuary, or the violent aftermath of giant children’s sandbox battles, marking the battlefield’s violence and horror. It was a strange and moving memorial.

Around and through this rusting sculpture garden the machinery of war progressed at a pace of steady frenzy. Trucks and tanks rolled from the bellies of high, blocky LSTs, the ships having pulled right up to shore before their bow doors lowered to burp out their gasoline-and diesel-powered cargo. Cranes lifted other cargoes clear, while army engineers drove bulldozers back and forth and military policemen kept a wary eye on the chaos of organization.

Feathered Dragon mt-3

Feathered Dragon mt-3 The Kinslayer Wars

The Kinslayer Wars Black Wizards

Black Wizards The Heir of Kayolin dh-2

The Heir of Kayolin dh-2 The Crown and the Sword tros-2

The Crown and the Sword tros-2 Realms of Valor a-1

Realms of Valor a-1 Wizards Conclave aom-5

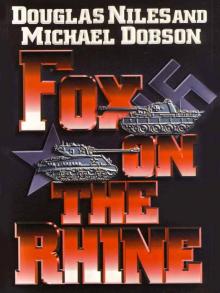

Wizards Conclave aom-5 Fox On The Rhine

Fox On The Rhine The Heir of Kayolin

The Heir of Kayolin Fox at the Front (Fox on the Rhine)

Fox at the Front (Fox on the Rhine) Measure and the Truth tros-3

Measure and the Truth tros-3 Emperor of Ansalon (d-3)

Emperor of Ansalon (d-3) The Messenger it-1

The Messenger it-1 The Druid Queen tdt-3

The Druid Queen tdt-3 Ironhelm mt-1

Ironhelm mt-1 The Dragons lh-6

The Dragons lh-6 The Last Thane cw-1

The Last Thane cw-1 Circle at center sc-1

Circle at center sc-1 Secret of Pax Tharkas dh-1

Secret of Pax Tharkas dh-1 Fistanadantilus Reborn ll-2

Fistanadantilus Reborn ll-2 Viperhand mt-2

Viperhand mt-2 Kagonesti lh-1

Kagonesti lh-1 The Druid Queen

The Druid Queen Lord of the Rose tros-1

Lord of the Rose tros-1 Goddess Worldweaver sc-3

Goddess Worldweaver sc-3 Eyeball to Eyeball (Final Failure)

Eyeball to Eyeball (Final Failure) Darkwell

Darkwell Fate of Thorbardin dh-3

Fate of Thorbardin dh-3 The Coral Kingdom tdt-2

The Coral Kingdom tdt-2 Wizard's Conclave

Wizard's Conclave The Coral Kingdom

The Coral Kingdom Winterheim it-3

Winterheim it-3 Emperor of Ansalon v-3

Emperor of Ansalon v-3 MacArthur's War: A Novel of the Invasion of Japan

MacArthur's War: A Novel of the Invasion of Japan The Fate of Thorbardin

The Fate of Thorbardin The Rod of Seven Parts

The Rod of Seven Parts Fistandantilus Reborn

Fistandantilus Reborn Prophet of Moonshae tdt-1

Prophet of Moonshae tdt-1 The Golden Orb i-2

The Golden Orb i-2